|

|

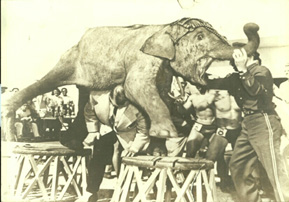

Milo lifting an eight hundred pound elephant

at the |

CWF #15 Page #2

Steinborn continued to amaze with his feats of strength. In 1924, he did an unassisted squat with 552.5 pounds. In a 1937 issue of Strength & Health magazine, it was reported that Steinborn had done several reps of deep knee bends, unassisted, with 408 pounds.

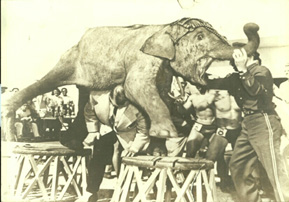

Steinborn’s strength was now legendary. He would perform a feat at the 1950 Chicago World’s Fair that made national headlines. While attired in his finest dress suit, Steinborn lifted an 800-pound elephant with a backlift, raising the giant pachyderm two feet off the reinforced stools that it was positioned on. "I was there with my dad at the World’s Fair," said Dick Steinborn. "Just before the lift, the elephant took a big crap, and the entire audience moved back several feet. The guy who was doing the announcing got on the microphone and told everybody that my dad was still going to lift the elephant, but the elephant now weighed twenty pounds less." Other strongmen at the fair attempted this feat, but none were able to match Steinborn’s accomplishment. What made this even more incredible was that Milo was fifty-seven years old at the time. This feat would also make the newspapers, appearing in "Ripley’s Believe It Or Not!"

|

|

Milo lifting an eight hundred pound elephant

at the |

Milo continued to wrestle sporadically, eventually winding down his career in the early 1950s, having his last matches in Florida. "About 1953, my dad and I wrestled as a team in Daytona Beach in a tag match against Pedro Godoy and Cue Ball Rush," remembered Dick Steinborn. "Rush died in the dressing room shortly after. It was either this match or one in Orlando shortly thereafter that was his last, where he wrestled Don Kalt, who was better known as Don Fargo."

Even in his seventies, Steinborn would amaze people, still doing squats with four hundred pounds. At ninety years old, Steinborn would squat with 125 pounds. In 1987, The Oldetimers Barbell & Strongmen Association awarded ninety-three year old Milo Steinborn with a plaque as a sign of appreciation for his lifelong contributions to the Iron Game. "They’ll never be another Milo," reminisced Dick Steinborn, "he really was beyond any comparison."

The Promoter

In 1948, Steinborn moved to New York to work with promoter Al Meayer, but after some convincing from Rudy Miller, he joined Miller and Toots Mondt and formed The Manhattan Booking Agency. "Miller had the money, and my dad had seen Al Meayer pull some pretty shady things, so he decided to hook up with Toots and Miller. Wrestling shows were being presented in the New York and New Jersey areas and the beginning of Dupont live television boosted attendance throughout the area," recalled Dick Steinborn. "The wrestling promoter in Buffalo, Pedro Martinez, always wanted to control the Big Apple. After the right offer, Martinez bought out my dad, Miller and Toots Mondt, taking over the Manhattan booking agency. Toots doubled back to New York, taking Antonino Rocca and Kola Kwariani with him. Milo then headed for Richmond, Virginia where he hooked up with Promoter Bill Lewis. That lasted two years. My dad had known Bill for many years, and went down there and refereed for him and took care of the matches. Bill was illiterate, so my dad was a big help to him. But, Bill didn’t take care of the boys and a lot of people didn’t like him." Steinborn had decided the time was right to leave Virginia and move on, and a phone call to an important promoter in the Sunshine State was about to change the landscape of Central Florida wrestling.

Orlando

"Milo called Florida wrestling promoter, Cowboy Luttrall, and asked if he had a town for sale," remembered Dick Steinborn. "Cowboy sold Milo Orlando for $1000.00. The weekly attendance was no more than 130 to 200 people at the time." Steinborn began holding shows at the American Legion Arena on the shores of Lake Ivanhoe, and would struggle the first eight months, barely making ends meet. Eventually, Steinborn would start drawing record crowds, with fans often being turned away. "My dad was a great promoter," said Dick Steinborn. "He really had a mind for the business. One time, in the early 1960s, Wilbur Snyder came down for a couple of weeks. He talked to my dad about wrestling because he wanted to make it a ‘working vacation’ so he’d be able to write it off on his taxes. Well, Snyder was booked with Ray Villmer, I think it was in Orlando. He told my dad that he was only in town for a quick trip, so he offered to put Ray over. To Wilbur, it made sense to put the local guy over. My dad told Wilbur ‘No, I want you and Ray to go broadway so you can educate the fans. It’s more important that they see great wrestling and learn something.’ My dad didn’t feel that it was important which wrestlers won and lost. It was more important to educate the fans about great wrestling…and he loved broadways."

Steinborn also operated a gymnasium just north of Downtown Orlando, at 2371 N. Orange Avenue. "Dad originally wanted a warehouse to put all his stuff," recalled Dick Steinborn. "But the gym became very popular with wrestlers and weightlifters all over Central Florida. We had the gym from 1960 to 1971. Dad would do all kinds of unbelievable things in the gym and the younger guys couldn’t believe what he was capable of."

The crowds continued to grow, and after Central Florida’s major interstate, I-4, opened in 1958, more people were showing up on Monday nights to see Milo’s shows. By 1966, with a burgeoning population in Orlando, as well as a turn-away business at the American Legion Arena, Steinborn was being advised by those closest to him to look into securing a new home for his wrestling cards. Enter Pete Ashlock.

Grover C. "Pete" Ashlock moved from Texas to Orlando in 1951 with $38,000 in his pocket and a desire to be his own boss. Ashlock was a self-professed cowboy who had won several championships on the rodeo circuit, and was known as a friendly, but tough man. He also was known for wearing his signature cowboy hat, and was often described as looking like "The Marlboro Man." In 1966, Ashlock would break ground on a land parcel on Econlockhatchee Trail in east Orange County, promising a new facility for concerts and sporting events. The new stadium would also give Ashlock a chance to promote rodeo events, something that he'd wanted to do for years.

When Ashlock opened the Orlando Sports Stadium in 1967, Steinborn decided that it was the perfect venue to house his wrestling shows. "I was instrumental in convincing my father to leave the American Legion Arena, that was coming close to standing room only each week," recalled Dick Steinborn. "Dad was getting older by this time and was stuck in his ways. He didn’t want to change anything. Pete Ashlock gave me a tour of his stadium, and I was convinced that it was the place to be."

|

|

|

Pro wrestling's opening night at the Orlando Sports Stadium. Left to right: Challenger Eddie Graham, Gordon Solie,

longtime friend of Milo's Jim Kelly, |

The move to the Stadium proved to be successful. "I remember the first performer in that building was Louis Armstrong," said Dick Steinborn. "Dad’s first wrestling show at the stadium drew over $6,000. When you realize that was 1967, that was a lot of money to be bringing in. My dad was the last of the fifty-fifty promoters. Luttrall, and then Graham, owned the territory. After expenses in Orlando, such as rent and booking, the remainder was split fifty-fifty between my father and the office. Earlier, the Tampa office had decided to become sole promoters of all the towns with the exception of a few."

Steinborn would also promote shows in other Florida cities like Eau Gallie, Leesburg, and Ocala. "Those towns were open," remembered Dick Steinborn, "and my dad had a trailer built to haul his ring. They weren’t going to bring that ring up from Tampa, so he was the first to start promoting in those towns. Ocala and Eau Gallie drew around five hundred people on average, but Leesburg averaged 1,000."

The relationship between Steinborn and Ashlock was beginning to show the signs of strain. Ashlock had been promoting boxing events and numerous fighters since the 1970s, often losing huge sums of money trying to keep the sport from going down for the count in Orlando. "Pete was getting greedy, trying to get money any way he could. After ten years of free parking, he decided that he was going to start charging people to park their cars," recalled Dick Steinborn. "Pete also wanted to take out a loan on the building to get some repair work done. He was trying to force my dad into co-signing the loan, but dad wouldn’t do it. He didn’t own the building, Pete did. Eddie Graham had also brought in Lester Welch to book. Lester was useless in my opinion. He was a rodeo guy, just like Pete, and they got together and conspired to steal the promotion from my dad. My dad smelled a rat. He and Lester didn’t see eye-to-eye, and Lester and Pete just pushed my dad to where he couldn’t take it anymore. The fun he got out of it was gone. My dad said the days of handshakes were over."

|

|

|

Milo demanding Dale Lewis return to the ring,

while |

Milo, after promoting wrestling in Orlando for twenty-five years, and missing only five shows, walked away from the business. "Pete Ashlock was not the man he presented himself as," said Dick Steinborn. "He over financed himself, and pulled some shady maneuvers to steal the wrestling promotion in Orlando. It was too obvious to everyone, and my father gave a 4-week notice to Tampa telling them they could have Orlando for free. That was after grossing $467,000 the year before. He couldn’t stand it anymore, so he just gave it back, without taking a penny in return. Dad had a great saying. He would use this at times when he would walk away from something. ‘When there is a pile of crap, don’t stir it, it stinks.’ Dad then said ‘Orlando is starting to smell bad.’

Ashlock finally threw in the towel on promoting boxing and deeded the stadium back to an Orlando bank in 1980. The bank then sold the thirteen-year-old arena to a Tampa group headed by Eddie Graham, of which Graham owned fifty percent. The Orlando Sports Stadium was quickly renamed the Eddie Graham Sports Complex, and Championship Wrestling From Florida continued to promote shows in the building until their demise in 1987. The building by this time had become antiquated, with newer and more modern facilities becoming available as Orlando continued it's expansion to compete with other major Florida cities.

The building was closed in 1993 by the Orange County Building Department

because of code violations. Steps were taken to bring it to code, but permits

eventually were dropped and the land put up for sale. In 1995 after being on

the market for two years, an Orlando based developer bought the land from

Prudential Florida Realty for $800,000 which included the building as well as

the land.

Prudential initially tried to sell the Stadium and the land for use as a

facility, but the area had changed and was now surrounded by homes and

apartments. Those who owned houses in the area were against the Stadium being

re-opened, fearing traffic and noise problems. The Stadium, which had housed

wrestling and boxing for twenty years, as well as concerts by Led Zeppelin,

James Brown, and Elvis Presley, was marked for demolition and sadly, put to

rest in November of 1995.

The land is now home to a "cookie-cutter" housing development with all traces of the historic building gone. "I have a lot of memories from that Building and Orlando," reminisced Dick Steinborn, "and my dad was a real character. They threw the mold away when they made him."

The American Legion Arena, home to Steinborn’s weekly wrestling cards for thirteen years, and the building where in 1953 former world heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey refereed a match and knocked wrestler Jack Wentworth unconscious, was demolished in 1987. There are now several office buildings in its place.

Milo Steinborn continued to live in Orlando after retiring from promoting, maintaining a home on Nebraska Street in the historic downtown district. Many years earlier, after visiting a palm reader who told him that he'd live to be ninety-five, Steinborn had a watch inscribed on the back "H. Milo Steinborn, 3-14-1893. Expected departure: 1989." Milo passed away from natural causes on February 9, 1989. He was ninety-five years old.

Dick Steinborn retired from active wrestling competition in 1984 following an auto accident that left his spine twisted. Currently residing in Richmond, Virginia, Dick is a physical fitness consultant and runs a private gymnasium from his home. Dick Steinborn, the "kid" that grew up and spent his entire life around professional wrestling, is sixty-eight years young.

Pete Ashlock retired in the early 1980s. After a plane crash took the lives of his son and daughter-in-law in 1984, Ashlock took over the day-to-day operations of the family business, Crane & Equipment Rental, Inc. Ashlock passed away from heart failure while vacationing in Bar Harbor, Maine during the summer of 1988. He was sixty-five years old.

Special thanks to Dick Steinborn for his informative and captivating recollections (and for graciously accepting my late night phone calls!) Also, many thanks to Dick for the fantastic photographs that appeared with this article.

Dick Steinborn’s columns have appeared in Scott Teal’s "Whatever Happened To…" for close to a decade. Many of these columns can be found here.

For more information on the City of Orlando, Florida visit Orlando's website.

NEXT MONTH:

The Tragic death of Eric The Red

All questions, queries, and comments are welcomed at Manof1000holds@aol.com.